Though he never went to a university, Jonson was well educated. By self-study he had acquired wide and deep knowledge of classics. All the stories of ancient literature were open to him; and he was familiar not only with the perfect productions of the Greek dramatists, but even with the fragments that lay scattered among the works of the grammarians, The Case is Altered and Every Man in His Humour offer ample evidence that Jonson came to playwriting fresh from the study of Plautus and Terence.

Jonson appeared on the scene when the Renaissance had already made itself strongly felt, particularly in an ardent revival in the study of Greek and Latin classics. In the last quarter of the Elizabethan age was formed a literary circle consisting of the supporters of the classics. Sir Philip Sidney was one of them and exercised an influence which was almost supreme during his short life (1554-1586). Admirer of the classics, Jonson was greatly influenced by Sidney and carried forward his fight for classicism and earned the reputation of being “one of the first significant neo-classic critics.” His critical views are to be found in practically all that he wrote: in his poems and plays, notably, The Poetaster: in his prefaces and dedications to his plays; in his. Conversations with Drummond: and most of all, in his Discoveries.

The English literature in Elizabethan and Jacobian ages suffered from many ills which have been summed up in one word “excess”: excess of passion, excess of imagination, excess of expression. Even the great Shakespeare was not free from them. Jonson had grasped the value and usefulness of the classical tradition and, saw the peril that attended the native or romantic tradition which gave free reign to English poetry and drama. He found a cure for the ills in classicism. He advocated order and discipline in writing. He emphasized the need of “care and industry” He advised the writer never to be content with the first word that offers itself nor with the first arrangement in composition. That is, he wanted the writer to write well not by chance, but knowingly. He held that the writer should revise his writing repeatedly to arrive at the best. He should take care to use words with due regard to their intelligibility, for “the chief virtue of a style is perspicuity, and nothing so vicious in it as to need an interpreter.” He adds that perfection in style depends on a writer’s “choiceness of phrase, round and clean composition of sentence, sweet falling of the clause, varying of an lustration by tropes and figures, weight matter, worth of subject, soundness of argument, life of invention, and depth of judgment.”

Also Read :

- Compare Hamlet with Macbeth, Othello and other Tragedies

- A Short Note On The Use Of Imagery In Shakespeare’s Sonnets

- Prologue to Canterbury Tales – (Short Ques & Ans)

Jonson’s view of the structure of the plot is derived from Aristotle’s ‘Poetics’, Following the Greek critic, he says, ‘The fable (or plot) is called the imitation of one entire and perfect action; whose parts are so joined, and knit together, as nothing in the structure can be changed, or taken away, without impairing, or troubling the whole. “He also requires of the plot. “a certain proportional greatness, neither too vast, nor too minute.” He is of the opinion that the plot may have episodes and digressions like “necessary household stuff and other furniture”. In his view the episodes and digressions do not impair the unity of action. Jonson has endeavoured to follow up his precept in the construction of his own plots.

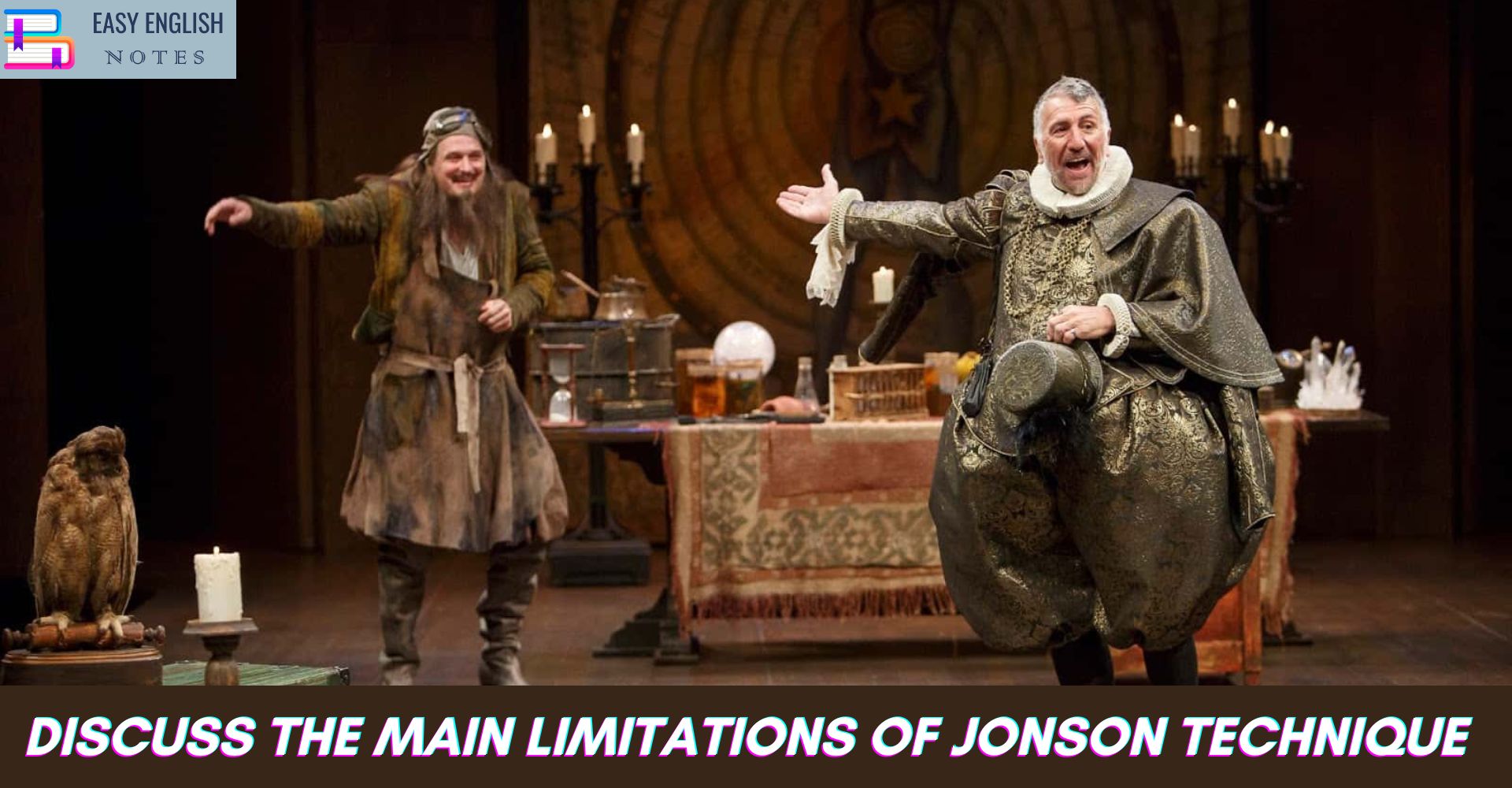

“Tragedy,” says Aristotle, “endevours, as far as possible, to confine itself to a single revolution of the sun. “But he says to casually and only once, and he nowhere insists on this as a condition of good plot. The Unity of place is not mentioned at all by Aristotle. But Jonson’s masters are of the sixteenth century, the Italian Castelvetro, the French playwright jean de la Taile, and above all, Sir Philip Sidney, who insisted on the observance of these two unities besides the unity of action. Jonson meticulously observes these unities, for example, in his Every Man in His Humour ‘Prologue’ is a manifesto enunciating Jonson’s whole-heard adherence to neoclassical doctrine.

Jonson’s classicism, however, has its defects too. What most discourages the reader of Jonson is the absence of charm. We move away with Jonson from the world of flesh and blood and permeating spirit that Shakespeare created towards an exhibition of automations splendidly constructed to perform their maker’s bidding; the high romantic temper of the Shakespearean comedy gives way to the artificial treatment of whims, freaks and ‘Humours’, the realism of Shakespearean tragedy and its universality are displaced in Jonson by learned frigidity. While reading Jonson, we rarely forget that it is only a play and dialogue. True to his classical program, Jonson ridiculed the abuses and fashionable follies of the time by making the persons of his dramas represent the peculiar hobbies or “humours” of men, but in doing this his drama lost faithfulness to life through a method which inclined him to make the mere caricature of what we call a “fad” take the place of a character. Jonson’s tragedies Sejanus and Catiane are massive, scholarly, and painstaking but they lack the warmth and humanity which distinguish Shakespeare’s treatment of classical themes, and one is apt to read. them with respect and with profit rather than delight.

Jonson, as we have noticed, set himself boldly to cure the theatrical evils of the time by establishing a comic and a tragic form based on classic example. In the latter endeavour he had no success; in the former he succeeded in making himself the greatest figure of his age.

This classicism of Jonson is best reflected in his Every man in his Humour. Jonson here tries to harmonize medieval medical conceit with the methods employed in the Latin theatre. For the middle Ages the “humours’ or natural moistures of the brain governed a man’s nature; too much of one, or shifting of the due proportions governing normality, would produce eccentricity of one sort or another. Thus, melancholy, greed, timorousness, choler, all were ‘humours’, and the persons who exhibited any of these was described as ‘humorous’. It is quite obvious that if art is to make use of these humours, the artist, must deal with a type, not with a personality. This was what Terence did in his dramas. His testy old fathers are all the same, his cunning slaves have all the same features; he picks up some salient features of a class of men and pictures them in his characters. Jonson, being a classicist, determined to follow this method. Besides this, Jonson also decided to follow in practice another old classical dictum. The object of the classical comic dramatists was to ridicule the vices of men, put folly in a foolish shape before the spectators and so laugh out the audience into good behaviour. Jonson too determined that his comedy should be a satiric comedy; and for that purpose the humours gave him the very tool he required.

Opposed to the romantic portraiture of “monstrous” Jonson concentrates on characters congruent with the setting, on the creation of literary types:

Persons, such as comedy would choose,

When she would shew an image of the times,

And sport with human follies, not with crimes.

Jonson’s characters are all based on the Greek medical theory ascribed to Hippocrates, who lived in the fifth century. B.C. He taught that “the body is composed of four cardinal ‘humours’, or Juices-blood, phlegm, yellow bill and black bile. When these are out of balance, disease results.” Jonson’s characters are all based on this theory. He says that “the purpose of comedy is to note those elements in human character, which either naturally and permanently dominate in each man, or which, on occasion, in the hazard of life, overflow and exceed their limit at the expense of the other contributing elements; to note this in a number of characters differently humoured, and in the clash of contrasts, to point, with pleasant laughter, the “moral’ of these disorders. And this is the purpose Jonson sets before him in writing his comedies. And this was what, Terence did in his dramas. His testy old father’s are all the same, his cunning slaves have all the same features. He picks up some salient features of a classicist, determined to follow this method. He had another reason, too. The object of the classical comic dramatists was to ridicule the vices of men, to put folly in a foolish shape before the spectators, and so laugh them out into good behaviour. For this purpose the “humours” gave Jonson the very tool he required. True to his classical program, Jonson, ridiculed the abuses and fashionable follies of the time by making the persons of his drama represent the peculiar hobbies or “humours” of men and women.

Another aspect of Jonson’s classical temperament was him zest for moral justice. He viewed himself as a moral satirist. If the comedies of the contemporaries of his early days affected any beneficial purpose. if they led to exposure and detestation of any evil quality, or the correction of any prevalent folly. It was by accident, not design; but with Jonson thin was the primary object. We see it in the first play which he is known to have written.

Jonson did not love the classics for their own sake. He loved English more. But it was English raised to the excellence of Greek and Latin. With this noble end in view he applied himself assiduously to the service of English Literature, particularly drama. Nevertheless, classicism did not do him that good which romanticism did to Shakespeare. We move away with Jonson from the world of flesh and blood to the artificial treatment of whims, freaks and “Humours”. The realism of Shakespearian tragedy and its universality, in short, are displaced in Jonson by what may he termed as learned frigidity.

Jonson set himself boldly to cure the theatrical evils of the time by establishing a comic and a tragic form based on classical example. “In the latter endeavour he had no success; in the former he succeeded in making himself the greatest figure of his age.

Classicism of Ben Jonson, Jonson followed the classical technique, which means the strict observance of three unities of time, place, and action, symmetrical structure of the play: exclusion of extraneous matter, no admission of any comic element into the tragedy. Against the freedom and license of the romantics he set up the classical restraint, order and harmony. The result was that the plays were constructed on more or less mechanical principles and we find less of life, colour and movement in his plays than in those of Shakespeare. He may realistically paint certain phases of London life, but we miss the broader horizon of Shakespeare’s plays- comedies or tragedies, in which more is meant than meets the eye. What Shakespeare paints of life, has its relation to the whole; we feel ” cabin’d ” in the atmosphere of Jonson comedy or tragedy. His humour is of a limited character. The large-heartedness of Shakespeare’s pity is wanting here. His own temperament which was narrow and one-sided could not have fitted him to move freely in the romantic atmosphere. The classical model was a matter of necessity to him-not a matter of choice. The following of the classical technique made his tragedies flat and stale. In his tragedies he went to distant ages and periods, marshalled by his accumulated learning; they could have been of more interest to the people of those ages than to the Elizabethans of Jonson’s own contemporaries. With his classical technique he was able to create new type of comedy, and it had little of defect on the point of construction and dramatic propriety; if though it lacked some living force, it held the stage because it dealt with contemporary London and London life. Jonson revived the classical form, but he could not have revised the classical spirit. If his comedy was related to the life of the times in a sense, it failed to capture the essence and meaning of life as a whole.

It has been the practice of Jonson’s biographers to institute a comparison between him and Shakespeare. These parallels have not been in all cases much favourable to Jonson. Naturally, Shakespeare is best set off by throwing every object brought near him into shade. Shakespeare wants no light but his own. As he has never been equaled, and in all human probability never will be equaled, it seems an invidious employ, at best to speculate minutely on precise degree in which others fell short of him.

The difference between Jonson and Shakespeare are obvious and fundamental. Jonson’s work as a whole is barren, more prosaic, more learned, and more laboured than Shakespeare, while he remains true to life, yet contrives to invest his mimic world with a magical atmosphere of beauty and romance. But Jonson is a realist. he presents the life of his time, but especially the low offer of Elizabethan London, with a hard, dry literalism. His object in his comedies was didactic. He thought that the poet’s mission was to point a moral and to reform society. He ridiculed the abuses and fashionable follies of the time by making the persons of his drama, represent the peculiar hobbies or “humours” of men’s. But as a result of this, Jonson’s plays lost in faithfulness to life through a method which inclined him to make the mere caricature of what we call a “fad” take the place of a character. The method of Jonson great as he was, was thus a distinct falling off from that of Shakespeare. Jonson’s tragedies, “Sejanus’ and “Catiline’ are massive, scholarly, and painstaking, but they lack the warmth and humanity which distinguish Shakespeare’s treatment of classical themes, and one is apt to read them with respect and with profit rather than with delight.

It was Jonson, who in his own time and even afterwards provided the typical antithesis to Shakespeare. He was more original than Shakespeare. Shakespeare accepts the conditions of the stage of his time, is aware of its shortcomings, but resigns himself to them with a smile. His relation with his public remains of a sympathetic nature. Jonson, however, adopts a different attitude. he is an angry and arrogant opponent to the Elizabethan stage; and he sets up his own tastes, ideas, and theories, all derived from the ancients, against the popular taste.. While Shakespeare follows with docility the course of the stream, Jonson filings his vast bulk against it.

But Jonson’s arrogance is often rather cumbrous. The approval which Jonson constantly claims from his audience and his ill-will to everyone and everything and faith in himself in contrast to the modesty with which Shakespeare invariably sinks his personality in his work, is never to be found or seen elsewhere.

Unlike Shakespeare, Jonson deals with human life in sections rather than as a whole, being content to satirise manners rather than to paint men and women. In his drama, he is a moralist first and foremost, afterwards the artist. T.S. Eliot has wonderfully brought out this difference between Jonson and Shakespeare in a few words: “Whereas in Shakespeare, the effects due to the way in which the characters act upon one another, in Jonson it is given by the way in which the characters fit in with each other.”

A further difference may be observed in Jonson’s treatment of London life. In fact, there is no more elaborate painter of London life than Jonson. Shakespeare paints with a bigger brush, but for detailed effects Jonson is supreme.

Jonson’s purpose is quite different from Shakespeare’s in his Roman plays. He sent himself a historical and political problem to solve, and it is essential to his purpose that the Romans should have felt and thought as he represents them. To Shakespeare, this was unimportant; he was representing human being independent of race or period. For this reason, the domestic side of his persons is always clearly indicated, while Jonson’s Romans live entirely for their public careers.

Next, when Shakespeare’s mind passes into gloom and bitterness, the resulting satire is directed at the universal qualities of men. Jonson, however, is seldom a universal satirist; he is generally either a public satirist, lashing at or mocking the fraud or the affected ‘humors’ of his day, or a private satirist, assailing his personal enemies with eager scorn and obloquy. The sense of humour which was so gay in Shakespeare, it hopelessly lacking in Jonson. Shakespeare is the greatest of all humorists, and Jonson has not much claim to be one, for his temper was unsympathetic and his intellect, though strong, was a little coarse.

“The distinction between the plays of Shakespeare and the plays of Jonson is clearly to be seen when we glance at the development of the dramatic productivity of each. Humour (of Shakespeare), as it advances, tends to become more mellow; moving either towards increased kindliness or towards excessive meditation of a highly contemplative kind; satire (of Jonson), on the other, hand, tends to grow more bitter and more severe. Humour many end in Melancholy; satire nearly always ends in pessimism. Whereas in Shakespeare’s work we see a continued kindliness and, at the close of his life, a melancholy contemplation of the shadows and of the shows of life, in Jonson we find a regular progression from the comparatively genial atmosphere of ‘Every Man in his Humour’ to the bitterness and the unconcealed contempt of “Volpone.”

– (Allardyce Nicoll)

This comparison between Jonson and Shakespeare may be appropriately concluded with Harry Blamires’s comment on the two playwrights:

“Through the seventeenth century Ben Jonson was considered by some to be England’s leading dramatist and by many to share an equality with Shakespeare. It is sometimes said that he has now been unjustly overshadowed by Shakespeare; but his plays lack certain qualities which have made Shakespeare’s appeal a lasting one. In particular Shakespeare’s poetry makes a profound exploration of the connotative, associative and symbolic power of words and consequently operates at a level of human interest that transcends historicity and topicality. No one would claim this gift for Jonson to anything like the same degree.” (A Short History of English Literature).

PLEASE HELP ME TO REACH 1000 SUBSCRIBER ON MY COOKING YT CHANNEL (CLICK HERE)